Airbnb launched its New Zealand office in 2015, and quickly fundamentally altered the landscape of residential-based tourist accommodation, becoming the most popular site for short-term rentals with approximately 1800 rentals listed on Airbnb in Thames-Coromandel district alone. This figure doesn’t include the other popular platforms such as Bookabach, Bachcare, Booking.com and others. Drilling down into 2018 Census data, Mercury Bay North had 702 occupied dwellings and 1,965 unoccupied dwellings, while Mercury Bay South had 492 occupied dwellings and 618 unoccupied dwellings. So, for the wider Mercury Bay area, that’s 1194 houses that are lived in, and a whopping 2583 houses that are not. In my little street alone, there are 18 houses, of which just 6 are occupied. Prior to the advent of Airbnb in Aotearoa many of these dwellings were holiday homes, but a proportion of these were in the long-term housing market.

It’s a complicated beast, this Airbnb thing: in some ways it can be argued that the provision of short-term accommodation helps to contribute to the tourism economy, especially in the wider Mercury Bay area, as well as helping individual property owners earn some additional money; and given that Mercury Bay is predominantly a lower-income area, every bit helps, right? But in other ways, it also hinders the tourism economy: at a time of record-low unemployment, many tourism and hospitality businesses are really struggling to get staff, and one of the contributing reasons for this is that accommodation is so hard to get (and if you can get accommodation, it’s really expensive). It also impacts established businesses such as motels, camping grounds and holiday parks.

So, let’s unpack these perspectives a little. In terms of providing short-term accommodation, Mercury Bay has a wide range of motels catering for quite up-market tastes through to holiday camps and cheaper family-friendly options. Very seldom are these filled to capacity (with the occasional exception of specific events such as the Summer Concert). Taking this view, Airbnb takes business away from established businesses in the area, rather than filling a need in the accommodation market.

Additionally, across the motu, local authorities have significant trouble knowing how to deal with Airbnbs – should they be rated as commercial properties or pay additional levies? Such regulatory moves are fiercely contested by Airbnb, and obviously aren’t popular with hosts. However, moteliers (who are subject to additional costs like fire and safety compliance and commercial ratings) see the current disparity between their compliance costs and those running Airbnbs as an unfair playing field. Consequently, Airbnb is often viewed as problematic for the tourism sphere, because it disrupts the trade of traditional accommodation providers such as motels and holiday parks, as well as posing legal and regulatory difficulties for local authorities.

The rhetoric employed within Airbnb suggests a significant contribution by Airbnb to the financial security of New Zealanders. The Airbnb website tells me I could earn $1317 a week on Airbnb. Attractive, right? I’d never get anywhere near that if I rented my house out. But is it realistic? There are undoubtedly a number of hosts who make a secure living through Airbnb; however, reports from within Aotearoa, as well as from international research, suggest that those who are able to make a living from Airbnb tend to be people who have high-end, expensive properties, or who act as professional hosts, co-hosting for others. A 2018 report by Deloitte Access Economics (prior to Covid and at a time of high tourism in Aotearoa) states that the median income earned by Airbnb hosts across Aotearoa is a mere $4,400 per annum. Given the conditions of this summer, both financial and weather-wise, it’s a safe assumption that this year’s figures will be significantly less. And that’s not considering the costs of running an Airbnb – not just the electricity, cleaning costs, any renovations you might have/want to do to make your place more appealing, but also your labour: mahi such as cleaning the toilet and bathroom, washing the linen, and so on.

During my PhD research on Airbnb a few years ago, many participants told me that long-term tenancies were problematic: compliance with tenancy laws, bad tenants and so on. And sure, there are bad tenants. But there are also great tenants, and a decent vetting process helps you find good people that will treat your property as their home – with pride and care – because a long-term tenancy means that it is their home! My personal view is that long-term tenancies help our town become more vibrant and connected, enable businesses to get the staff they need, help develop community relationships, add to social cohesion, and enable us all to live and thrive in a community.

It’s an attractive thought, being an Airbnb host. It has status (you’re now a micro-entrepreneur), there’s virtually no compliance compared to the drama of tenancy agreements and so on, and you get to earn some money. And it works well for some people, for sure. And if that’s you, great! But there are downsides to Airbnb hosting, just as there are up-sides to long-term tenancies. It’s worth thinking about, isn’t it?

– Words by Stella Pennell – PhD Sociologist

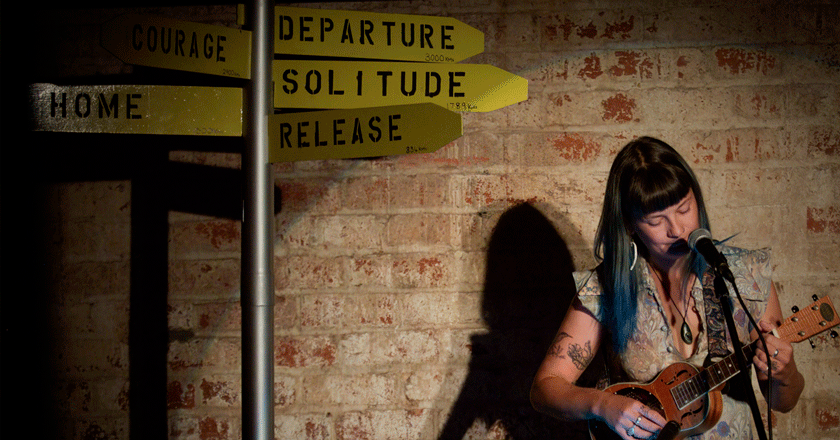

Art by Chloe Watts: www.blueberryco.co.nz