Curry, Karma, and Kindness

In 1975, after a three-week stay at a Buddhist monastery in Sri Lanka, I made my way by ferry across the Palk Strait to Tamil Nadu in southern India and from there caught a train to Pondicherry, a city south of the state’s capital Chennai, which at the time was called Madras. The name was changed in 1996, apparently to rid the state of the last vestiges of British colonialism.

Pondicherri fishmarket

Near Pondicherry, I wanted to visit Auroville, a yoga centre named after the spiritual teacher Sri Aurobindo and established in 1968 by one of his collaborators Mirra Alfassa, also known as ‘The Mother’. Their vision was to create a universal township that would contribute to the advancement of “humanity to its splendid future by bringing together people of goodwill and aspiration for a better world”.

Pondicherri fishmarket

Alfassa stated at the township’s opening, “Auroville wants to be a universal town where men and women of all countries will be able to live in peace and progressive harmony, above all creeds, all politics and all nationalities.

The purpose of Auroville is to realise Human Unity.” Imagine if all the great cities of the world adopted a similar vision.

There would be no room for many of the nutters in world leadership roles today.

Sri Lanka -Sri Maha Bodhi Viharaya Buddhist Temple

Auroville is situated on 20 square kilometres of desert, in the centre of which is a magnificent dome called the Matrimandir. It is the spiritual centre of the township, took 37 years to build and is covered in gold discs which reflect sunlight, giving it an ethereal glow. Silence is maintained inside to create a sense of tranquillity, something that the so-called ‘leaders of the free world’ may struggle with.

Sri Lankan fishermen

While spending some time in Auroville, I stayed in a coastal village five kilometres away and helped out teaching English at the centre’s Montessori School. I had met a young Indian guy who one night invited me to dine at his parents’ place in their small earthen thatched home. We sat on the floor and ate with our hands off banana leaf plates, but as I was about to put the first fingers full of food into my mouth a slap from my Indian host’s hand sent my food flying.

I was using my left hand which is normally used to wash the bottom after dropping a log.

Needless to say, toilet paper wasn’t widely used at that place and time.

I was unfortunately guilty of a grievous action which deserved the reprimand I received.

Train Station

A few days later, the school staff decided to have a party for the village children, with a feast, some games and some small presents for the kids. The people of the village were really poor, and I had already witnessed women physically fighting over their share of the tiny fish catch that their fishermen husbands brought to the beach on a bad fishing day.

But I was unprepared for the chaos that erupted during the party. What we thought of as ‘healthy food’ in the way of fresh salads and fruit and curry rice was prepared by the school staff and Indian helpers and was offered to the villagers, but little of it was eaten, due to it not being similar to their normal diet and definitely not spicy enough. Raw vegetables and salads were rarely eaten.

And then, when small presents were handed out to the gathered children, a free-for-all ensued with adults grabbing the gifts from the kids and guarding them jealously from other adult would-be thieves. What had been a well-intentioned celebration for the local village had turned into a noisy riot of arguing, shouting adults.

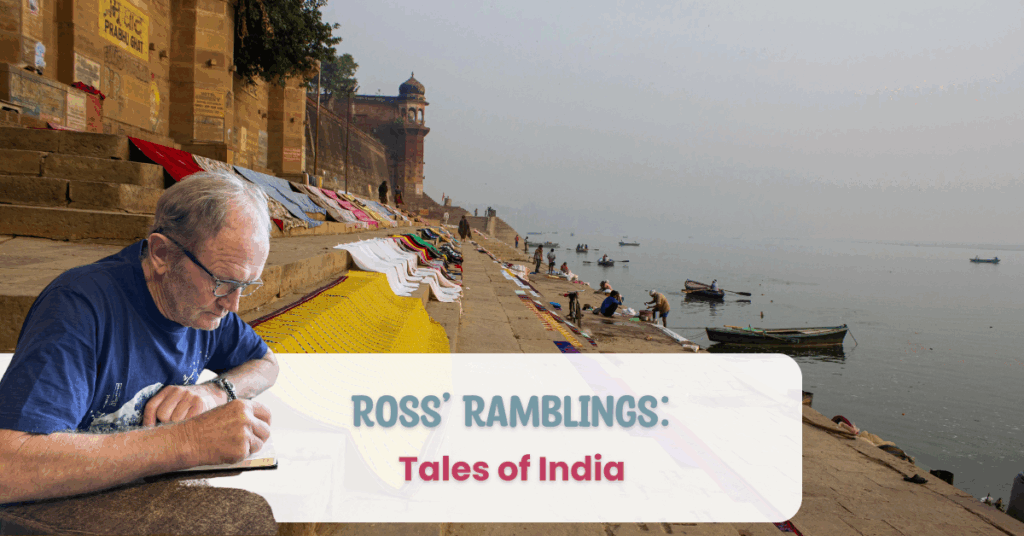

When my stay at Auroville came to an end, I boarded a 3rd class carriage of a steam train for the 1800 km journey north to Varanasi, the holy city on the banks of the river Ganges where many Hindus go to die in the hope of ending the cycle of rebirth and achieving nirvana. Varanasi is a noisy bustling city ironically seething with life in a place where people go to die.

The journey itself was extremely hard as we humans had to share the carriage with goats, chickens and, worst of all, bed bugs which came out at night and feasted on human blood leaving us scratching ourselves for days after. After 52 hours on that agonisingly slow train, we finally reached our destination, where long ghats or riverside steps allow easy access to the sacred river where Indians bathe and perform cleansing rituals. Two of the ghats are used as cremation sites. When a person dies, they are immediately washed by family members and covered with muslin cloth and decorated with flowers. Holy water from the Ganges is sprinkled on the body after which it is placed on a stack of firewood and cremated.

Varanasi

The head and feet were visible when I witnessed several bodies burning simultaneously. The heat caused muscles to contract and limbs to move and in one case a skull to pop which was a little disconcerting. When the fires died down, the ashes were scattered into the river while dogs scoured the cremation area for remnants of bone. I also saw bodies floating in the Ganges and was told by a local that lepers, children and pregnant women are among groups that cannot be cremated and are consigned directly into the river. Death at Varanasi was stark and confronting, very different from the sanitised crematorium experience so common in the west.

One night when returning to our accommodation in a busy street, a fellow traveller and I came across an old man lying on some cardboard on the pavement. People were just walking straight past him without offering help, ignoring his pleading eyes, so my friend and I bought some yoghurt and attempted to give him some nourishment, whereupon an obviously wealthy woman looked down at us and explained that the man was experiencing the karma of having committed bad acts in a previous life.

I looked up at the righteous sounding lady and wondered whether she would end up in a similar position in this life or a future one for not having displayed compassion.

The next morning, we were told that the old man had died during the night and had been taken away. I don’t know who cleansed his body or who paid for the firewood used at his cremation. Perhaps he was just quietly lowered directly into the Ganges.

Images by Lia Priemus – Facebook: PriemusPhotography Insta: priemus_photography

Words by Ross Liggins

Coromind: Coromandel’s Collaborative Magazine

Help us take Coromind Magazine to new heights by becoming a member. Click here

Change the Weather for Your Business: Advertise with Us.

Advertise your business in the whole Hauraki Coromandel in the coolest Coromandel Art Magazine, from Waihi Beach/Paeroa /Thames up to the Great Barrier Island.

Advertise Smarter, Not Harder: Get in Touch