An Acclimatising Society

What is Acclimatisation? It is the adaptation of animals or plants to an environment or climate they are not normally found in.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s first acclimatisers were the Polynesian voyagers that arrived here around 1250-1300 AD. They brought with them kiore (pacific rats), kūmara, kurī (dogs), taro and paper mulberry. The taro and paper mulberry did not grow well in this climate, but the kūmara grew well on our sub-tropical islands. The kiore and kurī, however, had a different impact on the environment. Many of the endemic birds here in Aotearoa New Zealand were flightless and so hunting was easy. Nests were often on the ground and therefore eggs and chicks were easy prey for these new mammals to our shores. This led to a loss of approximately 39 species, including nine species of moa, in the first 100 years of settlement.

The next wave were seafarers from Europe in the late 1700s, who liberated pigs and introduced potatoes as a new harvest crop.

Although the practice of taking animals and plants on migrations was thousands of years old, the mid-19th century became a time to transport these species to the ‘New World’. And so, the acclimatisation movement had begun.

An acclimatisation society was formed in Britain in 1860. This then became an official policy through the British colonies. Immigrants arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand believing in acclimatisation. This new country was an escape from overcrowded and industrial Britain and settlers saw the forests as being empty of game animals and the rivers lacking fish, with an eerie silence when the dawn arose.

These societies were set up around Aotearoa New Zealand; the members saw their role as providing the new settlers with the ‘home comforts’ of the old country. Farm animals, foods, timber, insect-eating birds, songbirds, pets, decorative plants, and fish and game were all introduced to make them feel more at home.

Some of these introductions have had a very negative impact on Aotearoa New Zealand and to this day we are battling these ‘pests’ of nostalgia.

In 1861, on one sailing ship came a feathered choir carried in eighty-one cages. The Cashmere cleared St. Katherine’s docks in London bound for Aotearoa New Zealand with cages of singing and game birds destined to be domiciled on the farthest side of the globe. These creatures had been collected under the direction of Mr Bartlett of the London Zoological Gardens, at the solicitation of the New Zealand Government. Some of those bird passengers were partridges, pheasants, blackbirds, thrushes, sparrows and Canadian Geese. Of 147 birds shipped, 88 survived the arduous journey.

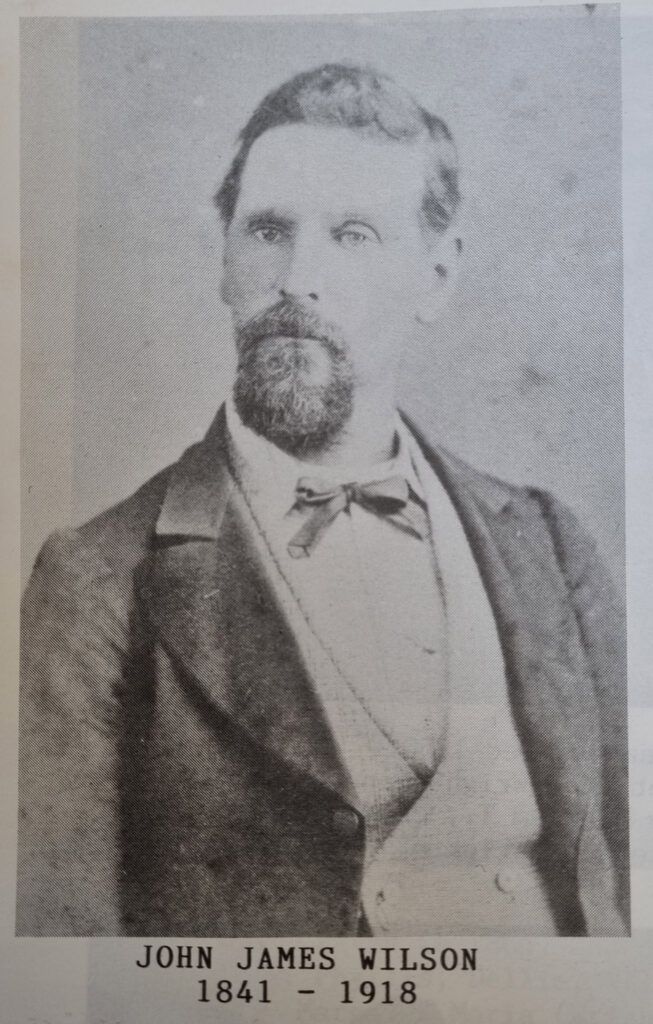

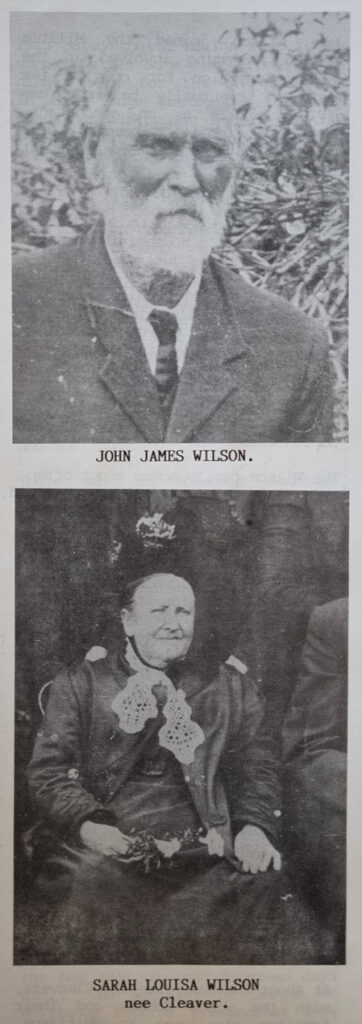

On board all of the birds were under the care of Mr John James Wilson, whose brother was the superintendent of natural history at the Crystal Palace. The ship set sail on December 9th 1861 and did not reach Auckland until April 8 1862 after a severe buffeting by storms in the Bay of Biscay. On arrival in Auckland the birds were warmly welcomed, and hundreds of people went to the wharf to view them. The birds were liberated on the properties of people who had volunteered to care for them. A pair of sparrows were kept in a cage in a grocer’s store on Victoria Road, Devonport for people to admire them.

Most of these birds prospered and became good settlers in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Mr John James (J.J) Wilson became a settler himself. He moved to Mahurangi and managed several general stores. In 1868 he married Sarah Louise Cleaver. Their first child, Catherine, was born in 1870 in Auckland, quickly followed by Edward in 1871 in Mahurangi. Their next eight children were Charlotte (1873), Ella (1876), Alfred Lupton (1880), Arthur Edmond (1883), John (1885), Frederick (1888), Louisa (1892) and Alexander George (1894). J.J and Sarah moved to Hikuai and then to Tairua in 1878 where he was a licensee for a hotel.

Catherine, their eldest child, married William Lee in 1889 and settled in Whitianga.

J.J finally settled into farming life in 1908 at Kaimarama, only to pass away ten years later in 1918. John James was survived by his wife Sarah and seven of his children.

-Words and Photos by Becs Cox

-Artwork by Berny Bee