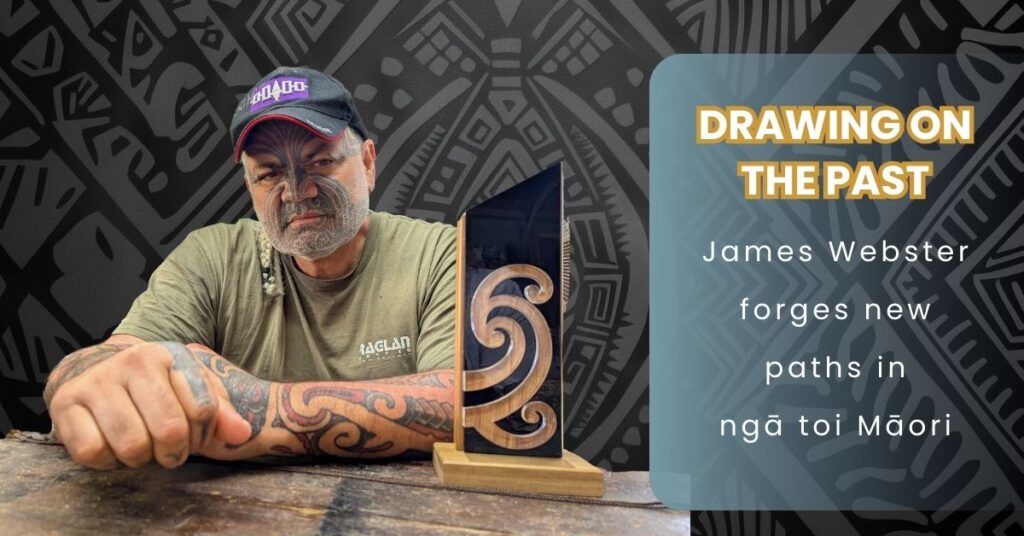

James Webster’s artistic journey is a testament to the power of self-discovery, whakapapa and cultural revitalisation.

When I arrive at his whare (home) on a sunny Sunday morning in Kapanga (Coromandel), he’s in his studio, hip-hop tunes blasting while he works at his desk. Stepping inside, I’m in a different world. It’s a large space with several workstations, tools and materials scattered around, carving works in progress, a bookshelf full of dried hue (gourds) and pūtātara (conch shell trumpets), more hue hanging from the ceiling, and photos and mementos from his travels.

Before we start, he gives a mihi to Coromind and to me for capturing some of his stories. I say ‘some’ because James has many stories to tell, and this article only scratches the surface. As I listen to him recollect his haerenga (journey), the wind rustles through the trees and tūī fly close to the studio entrance, singing their sweet song, eliciting a sense of connectedness to the rich indigenous roots of Aotearoa.

His story begins in Waikato where his whakapapa traces roots to the Pirongia maunga, the Waipa River and Pūrekireki Marae. Born to a Māori mother and a Pākehā father, James is a descendant of Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Apakura, and Ngāti Taramatau. His childhood was shaped by the dynamics of an urban life in Otahuhu, Auckland, the youngest of four children. His parents, like many others in the post-war era, were part of the urban drift, where Māori moved from rural areas to cities in search of new opportunities. As such, James’ exposure to his Māori heritage was limited, “… even back then I didn’t realise the cultural significance of being a Māori, I wasn’t bought up at the marae … in the classical Māori lifestyle.”

He recalls visiting his grandfather in Ōpunake and being intrigued by the photographs of tīpuna with tā moko (Māori tattoos). “I would get books and draw the faces … whenever we did get time to go to the marae, I used to be inspired by the whakairo, the carvings.

I remember hanging out by the carvings and running my hands over the textures.” As a teenager he played rugby league but was also drawn to creativity. “I loved doing art, I was always drawing and stuff. When I was younger I was influenced by Walt Disney … in my teens I started drawing alien muscle men and all sorts of weird stuff.” He was transfixed by Bruce Lee movies, drawing martial arts scenes, and had a natural affinity for woodwork. In 1980, he attended St Stephens boarding school in the Bombay Hills for three years, where he met Paki Harrison, a leading tohunga (teacher) of whakairo, and a key source of inspiration for James.

From there it was straight into trade training, “Coming out of school in 1982, pursuing a career as an artist wasn’t really an option,” he says. “It was all about getting Māori into the trades.” So he did a building apprenticeship which led him to work on a variety of building projects over several years, and included a move to Waiheke Island in 1988. On Waiheke, James connected with Piritahi Marae. The kaumatua, Whakaita (Kato) Kauwhata (Ngāpuhi) was very open, supportive and knowledgeable, “… he took a lot of us under his wing and gave us a tūrangawaewae, a place to stand”. James joined the marae committee but remembers reflecting on his role, “I wondered, who am I to be on this committee, making decisions for other people, when I didn’t really understand myself, and understand my relationship with my own Māoritanga or whakapapa?”

“… even back then I didn’t realise the cultural significance of being a Māori, I wasn’t bought up at the marae … in the classical Māori lifestyle.”

So in the early 90s, he embarked on a hīkoi around Aotearoa, visiting marae and immersing himself in Māori culture. In the South Island he connected with Te Huarahi O Rongo Marae Roa (Peace Trails), the Elkington whānau who were involved with constructing Te Awatea Hou – a 20 tonne, 30 m waka tangata for the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, and Mita Mohi (Te Arawa) who was running a mau rākau (Māori weaponry) wānanga in Akaroa, where James learned how to make and use taiaha. He returned to Waiheke Island in the mid-90s and started an art group to bring together Māori and non-Māori artists for themed exhibitions, “That’s where my creative spark was lit and the fire was stoked, but inside me, my wairua, it didn’t sit with me comfortably. To alleviate that feeling you can either run away from it or you can apply yourself”. So he enrolled in a te reo Māori course to elevate his understanding, followed by a move to Raglan to attend Te Ataarangi, a total immersion language nest in the Waikato.

In 1998, James decided to formalise his artistry and attended Toihoukura – School of Māori Visual Art & Design in Gisborne, which taught a variety of contemporary Māori art forms. After graduating, he spent nine months building a house in Whangaruru, before returning to Waiheke to pursue art full-time.

After his parents passed away in the early 2000s, he moved to Whitianga in 2005 to live in their whare, establishing strong connections with the local community and iwi, Ngāti Hei. Around this time he met his wife, Hinemoa Jones (Te Arawa, Tainui, Pākehā) – a storyteller, reo Māori educator and kaupapa Māori facilitator. After the couple had kids, James’ artistry really kicked in. He opened a small studio on Campbell Street, but quickly realised that a traditional ‘shopfront’ approach to art was not for him, choosing instead to work from home, and working on a commission only basis.

As their tamariki grew up, James and Hinemoa were keen on more kaupapa Māori opportunities like kura kaupapa (Māori language schools) for their children, but there were no options in Whitianga. It was then that they decided to move and settle in Kapanga, so their kids could attend Te Wharekura o Manaia.

This is my reality as a Māori in this country, connected to all these layers of whakapapa that have brought me to where I am … through your art you try and reflect that, give it a sense of meaning and purpose in the world. With every piece of taonga puoro, with every moko, with every waiata that you sing, there’s a story to be told and a kōrero to be had.

In the 12 years since moving to Kapanga, James has continued to push boundaries in his art practice. He works in a range of mediums, from tā moko, whakairo and taonga puoro (Māori instruments), to painting, mixed-media and public artworks. Hinemoa and James are especially passionate about reviving ancient Māori art forms, such as karetao (Māori puppetry), which they merge with taonga puoro to create a hybrid art form that blends sound, movement and storytelling.

James’ expertise in taonga puoro has led him to collaborate with musicians and artists from around the world, performing at prestigious events and recording music. He’s also a key member of Haumanu Collective, a group dedicated to the revitalisation of taonga puoro, and in 2025, he will release his first solo taonga puoro album!

In November 2024, James received the Creative New Zealand Ngā Tohu Hautūtanga Auaha Toi – Making a Difference Award, which recognises exceptional contributions to contemporary Māori art. For James, his work is more than just an expression of creativity; it is a way to connect with the past and forge new paths for ngā toi Māori. “This is my reality as a Māori in this country, connected to all these layers of whakapapa that have brought me to where I am … through your art you try and reflect that, give it a sense of meaning and purpose in the world. With every piece of taonga puoro, with every moko, with every waiata that you sing, there’s a story to be told and a kōrero to be had.”

To learn more about his mahi and enquire about commissions, visit:

Tahaa – Tā Moko & Māori Arts Studio

Words and photos by Anusha Bhana

Coromind: Coromandel’s Collaborative Magazine

Help us take Coromind Magazine to new heights by becoming a member. Click here

Change the Weather for Your Business: Advertise with Us.

Advertise your business in the whole Hauraki Coromandel in the coolest Coromandel Art Magazine, from Waihi Beach/Paeroa /Thames up to the Great Barrier Island.

Advertise Smarter, Not Harder: Get in Touch